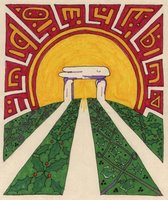

Last week on Dec. 21, the winter solstice, we had nine hours and four minutes of daylight. By Jan. 9, we will be getting all of nine hours and 17 minutes of day. While that's a far cry from the 15 hours and 17 minutes we'll have at the summer solstice June 21, the trend at least is comforting and full of hope of warmer times.

Last week on Dec. 21, the winter solstice, we had nine hours and four minutes of daylight. By Jan. 9, we will be getting all of nine hours and 17 minutes of day. While that's a far cry from the 15 hours and 17 minutes we'll have at the summer solstice June 21, the trend at least is comforting and full of hope of warmer times.

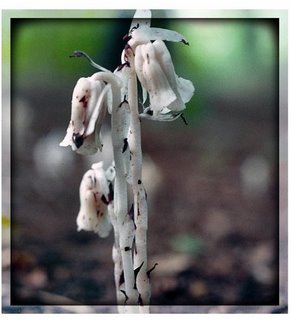

For many, the lack of sunlight brings on seasonal affective disorder, whose signs include depression, irritability, overeating, and lethargy. It shows that despite the lofty place to which homo sapiens has risen among the animals, we are still creatures of nature and subject to her powers.

In fact, seasonal affective disorder may be a sign that nature really wants us to be more like bears. We should just fatten up and find a nice warm cave for the winter.

Some people have found a substitute. It’s called Florida.