At least, that’s what old-timers believed, not only calling our early spring anemones “windflowers” but scientifically naming them after anemos, the Greek word for wind. In fact, in Greek mythology, Anemone was a breezy nymph who hung out with Zephyr, god of the west wind.

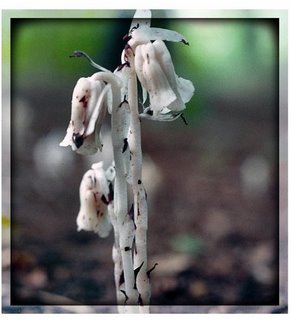

Wood Anemone and Rue-Anemone, two white buttercups of our April woods, could thank the wind for more than their names. Lacking much color or scent in a chilly season when few insects are about, they rely on the wind to disperse their pollen.

Wood Anemone and Rue-Anemone, two white buttercups of our April woods, could thank the wind for more than their names. Lacking much color or scent in a chilly season when few insects are about, they rely on the wind to disperse their pollen.

However, the naming gurus seem to have gone awry when labeling our common Rue-Anemone. The plant was long called Anemonella thalictroides, which literally means “a little anemone that looks like a thalictrum” – thalictrum being meadow rue, a summertime wildflower. But two decades ago, scientists reclassified the plant, deciding it really is a meadow rue and calling it Thalictrum thalictroides: “A meadow rue that looks like a meadow rue.”

Really!