Frederic and Mary Lewis:

The Showplace on West Lane

Ridgefield had many great homes early in the 20th Century, but few surpassed Frederic and Mary Lewis’s “Upagenstit,” an estate that town historian Dick Venus called “one of our nation’s showplaces.”

At one time this 100-acre spread on West Lane employed nearly 100 people. The house had more than 40 rooms, and the estate was equipped with an indoor swimming pool, immense greenhouses, and a dozen other buildings. Many houses were provided for workers – most still exist along West Lane, Olmstead Lane and on Lewis Drive. At one point, Mr. Lewis’s private physician lived in one of them and his personal chef in another..

His home was so big that, with little modification, it became a college in the 1940s.

Frederic Elliott Lewis was born in 1859 into a wealthy New York City family. He grew up in Manhattan and at a young age, began working for National City Bank, where his grandfather, Moses Taylor — one of the richest men in the 19th Century — was president (National City Bank is today’s CitiBank). Lewis was eventually elected vice president of the bank.

However, poor health forced Lewis to leave his banking career at a relatively young age, and he spent time traveling in Europe, resting in Florida, overseeing his investments, and generally

enjoying life. He was fond of yachting and at one point owned three steam-powered vessels, one of which was 70 feet long.

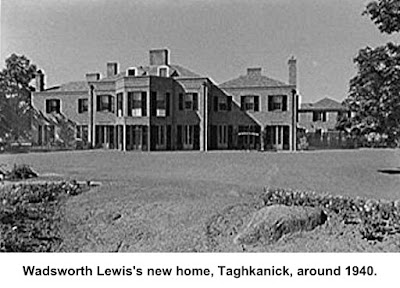

Mary Alice Russell was born in 1862 in Middletown, Conn., also to a very wealthy family, involved in international trade. She and Frederic were married in 1887 and had three sons: Reginald, who later had a gentleman’s farm on South Salem Road near the New York line, but eventually moved to an estate in Norfolk, Conn.; Wadsworth, who built an estate on Great Hill Road (and has been profiled in Who Was Who); and a third son, Frederic, who died when he was 11.

Frederic and Mary lived in Manhattan and maintained a summer home in Tarrytown for many

years, but in 1907, they decided to move farther from the city. They bought Henry B. Anderson’s estate on West Lane, west of High Ridge. The Lewises began making vast changes to the place, replacing Anderson’s house with a castle-like mansion and adding more land and many more buildings to what was eventually a 100 acre.

In 1934, The New York Times reported that the Lewises had spent nearly $2 million (some $54 million in today’s money) on the improvements at Upagenstit. They included:

- A network of paved roadways, lined with yellow brick gutters, at a time when none of the main roads in town were paved. Electric lighting was provided for many of the roads.

- Various barns and poultry houses for a stock that included Guernsey and Jersey cows, Berkshire pigs, and Plymouth Rock fowl.

- An ice house that could hold up to 3,000 cakes of ice, cut from their own pond and stored for the warm months. (A cake of ice could weigh more than 300 pounds; the foundation for the ice house was two feet deep and included a drainage system for melting ice.)

- Two tennis courts, one clay and the other grass.

- Specimen trees and shrubs from around the world — many of which are still part of the Ridgefield Manor.

- A stable that could handle 14 horses and a garage that could hold 15 cars.

- A fleet of automobiles that included Mary Lewis’s Rolls Royce that had flower vases on each side furnished with fresh flowers each day; it featured a speaking tube through which she could converse with the chauffeur (their estate had three chauffeurs).

- 2,000 feet of finished stone wall, mostly along West Lane and Golf Lane (and mostly still standing)

- A pond that still exists on western Lewis Drive (it later held the Ward Acres exotic waterfowl collection). A small octagon boathouse/bathhouse built by the pond was later moved to East Ridge to serve as part of the airplane-spotting facility during World War II. The building is now an office on Bailey Avenue.

- Last but not least, squirrel houses. According to The Ridgefield Press in 1908, “Mr. Lewis’s favorite pets are the tame gray squirrels, having brought about 50 from Tarrytown. There are special houses for these sleek, interesting little fellows. When Mr. Lewis gives his call, he is surrounded almost at once by them.”

Former town historian Dick Venus described the house, which had more than 40 rooms. “The

front entrance was most impressive and was protected by a very large porte-cochere, over which there was a parapet that gave it the effect of a medieval castle — and a castle it was. The massive entrance hall was open to the third floor, on the style of the Capitol, except that it was not rotund. Mr. Lewis liked everything square.”

The house included a dairy room, which had a cream separator, a butter churn, a bottle washing machine, and a “gigantic ice cream freezer.” Milk was provided by the estates herd of cows to make butter, cream and ice cream.

The laundry room was 40 by 30 feet in size. “It had the usual apparatus one would expect to

find in a laundry, but one thing made it unique,” Venus said. “It had a clothes drier and this was many years before the sophisticated, automatic driers of today. This drier was of simple design, but it did the job.”

The place was heated by two enormous furnaces, and had bins that could hold more than 60 tons of coal.

Dick Venus reported that every morning Mr. and Mrs. Lewis would go for a walk around their estate. While walking, Frederic “whistled constantly, in order that the people working on the estate would know that they were coming. He did not mind if they sat down again after he and Mrs. Lewis had passed by, but felt that they should give the appearance of being industrious while they were passing.”

The whistling was especially important to the workers in the cow barn. “One of their duties each morning was to listen for Mr. Lewis’s familiar whistle,” Venus said. “The whistle was their signal to unroll a large red rubber carpet that covered the platform between the cows from one door to the other. After the Lewises had passed through the barn, the carpet was rolled up to await the next visit.”

The Encyclopedia of Biography, published in 1922, described Frederic Lewis as one who

“interested himself keenly in many subjects.” He was a “man of great influence in many departments of [New York] city’s life, and he won and kept a host of friends who valued keenly his lovable and kindly personality and admired highly his sterling and virtuous character. His influence was always directed toward good ends, and his was one of those rare figures of which it may truly be said, ‘that the world is better off for their having lived.’ ”

He was also a generous man. “He was a friend of the worthy needy and he freely, but absolutely anonymously, has contributed largely to the relief of the distressed,” said The Press when he died in 1919 at the age of 60. “The extend of his philanthropic work will never be known as he never spoke of it and would not permit others to mention it. Many a worthy case that received timely help will never know the identity of their benefactor.”

Venus described him as “a very jovial individual, but for all his good nature, he was known to possess a vocabulary that would match that of a longshoreman, and when he felt that it fitted the occasion, he did not hesitate to use it.”

Frederic Lewis was not much involved in Ridgefield’s business and social life, though he did lend his banking expertise to the First National Bank of Ridgefield, where he served as a director (the bank, through many mergers, is now Wells Fargo).

Mary Lewis was more involved in the town. She was responsible for a work of art that visitors

to St. Stephen’s Church have admired for a century: The large stained-glass chancel window entitled “Christ Blessing the Children.” According to research done by parishioner James Carone, Mrs. Lewis commissioned the window in 1916, shortly after the church was completed, in memory of her mother, Clara Russell Bacon. Later, her father’s name, Samuel Wadsworth Russell, was added to the memorial. The window was fashioned by J&R Lamb Studio, America’s oldest continuously operated stained-glass company; it was founded in 1857, long before Tiffany’s, and is still producing stained glass works today.

Mary Lewis was also involved in the operations at St. Stephen’s, including helping get the parish out of a financial problem caused by a church treasurer who embezzled a sizable amount of money earmarked for the new building. She and her husband also contributed $19,000 of the $25,000 cost of the new church rectory ($19,000 then would be around $425,000 today).

Mary Lewis served as the first president of the Ridgefield Chapter of the American Red Cross, founded at the start of World War I, and held that post many years. She was vice president of the District Nursing Association (now Ridgefield Visiting Nurse Association) for 31 years.

Not surprisingly, Mary Lewis was a charter member of the Ridgefield Garden Club and involved in the club’s efforts to beautify the town. After all, she oversaw vast Upagenstit gardens and

mammoth greenhouses, working with estate superintendent John W. “Jack” Smith (see his Who Was Who profile). The Lewis estate produced many exhibits for New York City flower shows and won many awards, particularly for orchids. (As an interesting aside, Jack Smith’s obituary appeared in The New York Times. Frederic Lewis’s did not.)

With the Depression causing the family to scale down, Mary Lewis sold Upagenstit in 1934 to bridge expert Ely Culbertson and moved to Norfolk to live with her son, Reginald. She died in 1950 at the age of 87.

In the early 1940s, the estate became Gray Court Junior College, a school for women. The college opened in September 1941 with about 100 students and 15 faculty members and lasted until around 1945. The greenhouses were used for classrooms and the glass walls were praised in a college brochure for having the “obvious” advantages “to sight and health.” One section of greenhouses was called “Crystal Hall.”

By 1949, the place had turned into the Ridgefield Lodge and Health Resort, aimed at elderly visitors, and was becoming a source of considerable controversy. First, the Zoning Commission got after the operators, alleging that they were running an illegal home for the aged, rather than a resort or hotel. Then, when the operation became the “Ridgefield Country Club,” the New York state insurance commissioner maintained that the corporation that owned the place was using it as a secret Communist Party headquarters for underground “indoctrination” and “propaganda.”

Finally, a developer named Harold F. Benel bought the place in 1954, tore down the house and created a subdivision of 46 one-acre lots on 66 acres. He called it The Ridgefield Manor Estates and used Lewis’s driveways for Manor Road and Lewis Drive, adding Fairfield Court.

As for why the Lewises named their estate Upagenstit — “up against it” — no one is certain.